Fall fireflies

Three days in September

Lost in thought, I walk through the welcome coolness of a September evening, eyes fixed on the dusty road ahead. I scarcely notice the mountains that grace my western horizon, the lush clover field that runs alongside me to the north, the scattered ponderosa pines on the slope to my south. And then, suddenly, the world is in motion all around me. Small brown birds flitting, fluttering—flashing? As I raise my binoculars, I see a flash of bright yellow, then another, and another, and I realize I’m in the midst of a migrating flock of Yellow-rumped Warblers. Like the fireflies that illuminated my childhood nights, these luminous little birds stop me in my tracks and, for a moment, become my whole world.

To me, Yellow-rumped Warblers are birds of the coniferous forest. Their variable, warbling song is a subtle soundtrack to my summer hikes in western mountain country. So as I stand in the open and watch them frenziedly gleaning and pursuing insects, I relish the clear views of birds that are all too often obscured by forest foliage. They are in their drab nonbreeding plumage now, but as they move from fence line to ground to scattered trees, their diagnostic bright-yellow rumps catch the eye and confirm their identity. (This feature has earned these lovely birds the somewhat inelegant moniker butterbutts).

By now, I shouldn’t be surprised to see them in such an open habitat. Decades ago, while surveying for tortoises in the Sonoran desert, I saw flocks of wintering yellow-rumps foraging among creosote bushes, which dominated the desiccated landscape. I learned then that this opportunistic warbler inhabits a wide variety of habitats in the non-breeding season, from coastal scrub to shrubby deserts, from open forests to residential areas. In winter, yellow-rumps often travel in flocks and feed on berries. Their specialized ability to digest waxy berries (such as bayberry and wax myrtle) allows these hardy birds to overwinter farther north than any other warbler. And yet, even though I’m familiar with this versatile bird’s eclectic habits, I am still taken aback whenever I see them outside a forest.

The next evening, I am again surrounded by actively feeding yellow-rumps in the same open area. Whether this is the same flock taking an extra day to refuel along their journey or a second wave of birds, I can’t say. But once again, I stand amidst their chaotic activity, celebrating one of the avian gifts that make migration such a cherished season for bird lovers.

After two evenings of being surprised by Yellow-rumped Warblers, I should expect the unexpected. But when I look up from my computer the following afternoon, I am startled to witness a flock of them flashing their yellow rumps as they forage around my house. Flitting amidst the sagebrush bushes, dropping into the grass, fluttering up to the windows to snag insects, the resourceful birds turn cryptic food into fuel, enchanting me in the process.

For three days in September, these vibrant “forest” birds brightened my world and refreshed my perspective. As the month draws to a close, I lie in bed, looking up at the stars and relishing the sound of a bugling bull elk as he maneuvers his nervous harem through my field. Overhead, unseen, thousands upon thousands of beating wings power innumerable journeys through the night sky, transporting small forms toward more clement haunts. In my mind’s eye, I see the flash of those feathered fireflies—small beacons of hope—bringing light to a darkening world.

Take a small step to help birds

Birds are in crisis and need our help more than ever. According to the US Fish and Wildlife Service, over 96 million people in North America watch birds. If each of us does something (anything!) to help them, we may be able to reverse declining bird numbers.

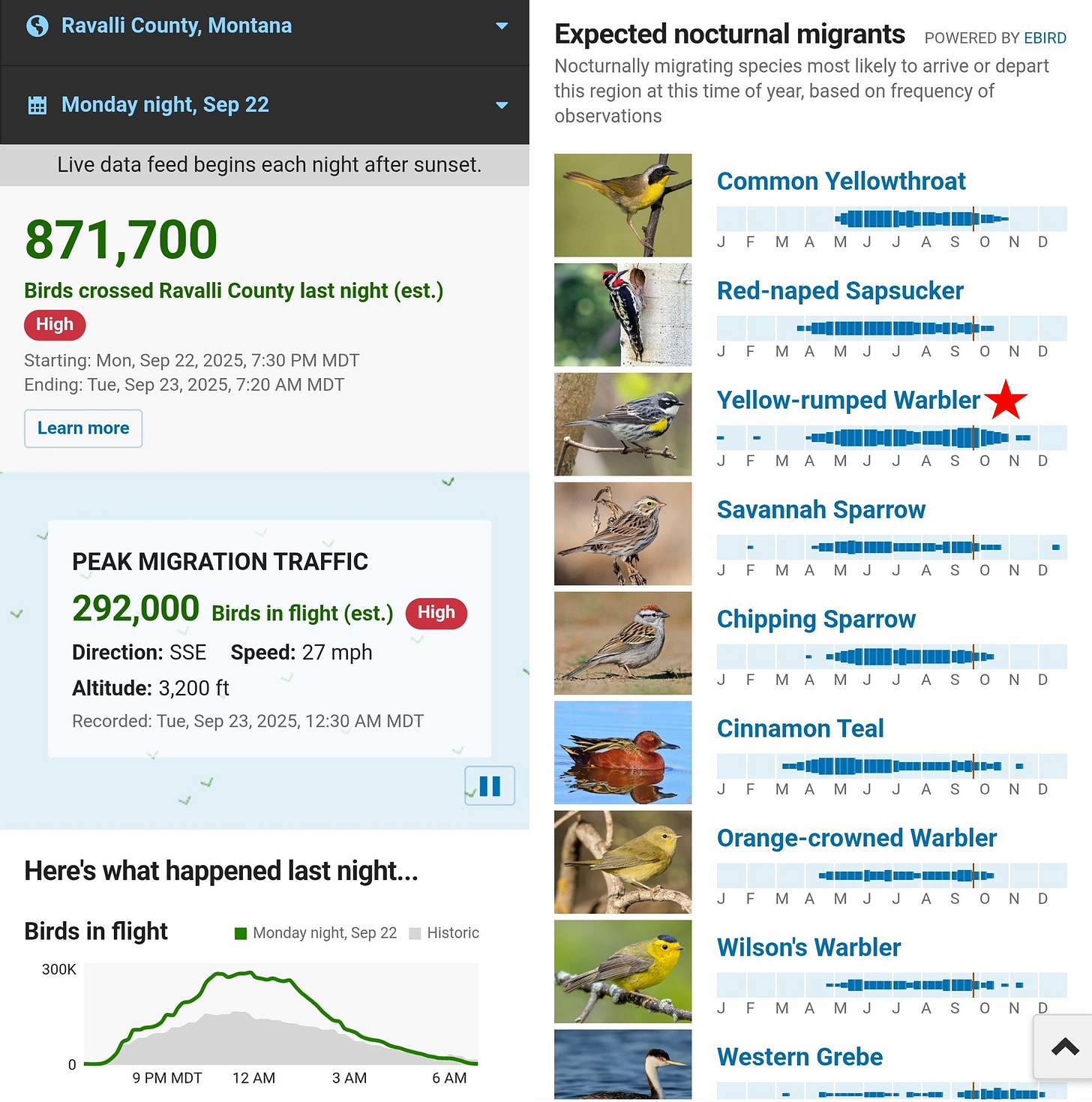

Hope is a better motivator for taking action than despair. If you need an infusion of hope, check out your local BirdCast (or bird forecast). Seeing how many birds are flying over your local county each night is a welcome reminder that birds are still here and we still have the power to turn their declining numbers around before it’s too late.

Night-flying birds are attracted to light and can be drawn into hazardous areas. Yellow-rumped Warblers are frequently killed by colliding with windows, radio towers, and other structures during migration. Minimizing outdoor lighting benefits wildlife at all times, but it’s critical for protecting birds during the migration season. If needed for safety, use motion-sensing or downward-pointing lights. Avoid solar-powered yard lights, turn off unnecessary lights in your home, and keep your shades drawn. A growing number of cities—like Dallas and Chicago—have taken measures to reduce the impact of night-lighting on birds and are calling upon their residents to help.

Many birds depend on berries to power their migration or to refuel during their journeys. If you have a yard, consider adding a native fruiting shrub or tree to your landscape during the fall planting season or make plans to do so next spring.

Until next time …

P.S. If you happen to read my new book Feather Trails—A Journey of Discovery Among Endangered Birds, please consider leaving a rating of the book on Amazon or Goodreads.

Oh, wow, Sophie! Another stellar post! I happily stumbled across this while wading through a pile of unopened emails, and, like your flocks of yellow-rumps, it was a very welcome and beautiful surprise!! Migration is such a miracle of nature, and each year, it astounds me that these tiny beating hearts clothed in feathers so steadfastly travel the skies, braving predators, inclement weather, exhaustion, glass windows, and myriad other dangers in their quest to move to and from breeding and wintering locales. What a wonder! And I won't ever look at a "Butterbutt" (though admittedly inelegant, I do love the nickname) again without also thinking of fireflies, which I grew up treasuring in Nebraska's mid- summer nights. Thank you for a most welcome reprieve in my morning!!

Lovely essay, Sophie!